|

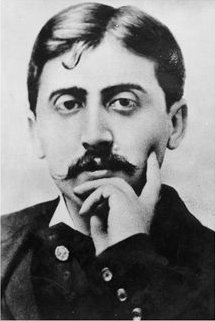

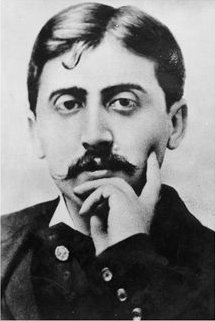

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust

(1871-1922), was a French novelist, essayist, and critic, best known as the author of À la recherche du temps perdu

(in English, In Search of Lost Time; earlier translated as Remembrance of Things Past), a monumental work

of twentieth-century fiction published in seven parts from 1913 to 1927, spanning some 3,200 pages and teeming with

more than 2,000 literary characters. "In 1893 Proust met Robert de Montesquiou [French Symbolist poet and art collector -- and all around snob] at the house of the hostess-painter Madeleine Lemarie... Montesquiou, a monster of egotism who needed constant praise as exaggerated as that which Nero had required, and who could be as sadistic as the Roman emperor if it was not forthcoming -- was thirty-seven when Proust, just twenty-two years old, met him... In his high-pitched, grating voice Montesquiou was constantly recited [sic] his own poetry... or presiding over literary and musical soirees. No praise was too extravagant, and Proust knew how to lay it on thick. 'You are the sovereign not only of transitory, but of eternal things,' Proust wrote him... But Proust was also the master of the nuanced compliments; after Montesquiou showed him his celebrated Japanese dwarf trees, Proust had the nerve to write him that his soul was 'a garden as rare and fastiduous as the one in which you allowed me to walk the other day ...' And Montesquiou heard that Proust kept his friends in stitches imitating his way of speaking, of lauging [sic], and of stamping his foot. Most daring of all, Proust proposed to write an essay to be titled 'The Simplicity of Monsieur Montesquiou,' who had never been previously accused of such a quality." 1 |

|

Review / Novel

(1907 / 1925):

"[Proust] was so impressed with the bonsai or Japanese dwarf trees that in 1907 he ordered three more from [the art critic and collector Samuel (Siegried)] Bing's when struggling to write a review of Anna de Noailles's Les Éblouissements. In the review and later in his own novel (Proust, Recherche, 3:130), he alludes to them as emblems of the immensity that can be held within a single line of poetry. Proust concisely and accurately identifies the chief aesthetic property of these Japanese arts when he replies to [his good friend and woman of letters Marie] Nordlinger, 'the Japanese dwarf trees at Bing's are trees for the imagination' (quoted in Painter, Proust, 1:3). In the review he wrote: "'Je ne sais si vous me comprendrez et si le poète sera indulgeant à ma rêverie. Mais bien souvent les moindres vers des Éblouissements me firent penser à ces cyprès géants, à ces sophoras roses que l'art du jardinier japonais fait tenir, hauts de quelques centimètres, dans un godet de porcelaine de Hizen. Mais l'imagination qui les contemple en même temps que les yeux, les voit, dans le monde des proportions, ce qu'ils sont en réalité, c'est-à-dire des arbres immenses. Et leur ombre grande comme la main donne à l'étroit carré de terre, de natte, ou de cailloux où elle promène lentement, les jours de soleil, ses songes plus que centenaires, l'étendue et la majesté d'une vaste campagne ou de la rive de quelque grand fleuve.' ("I do not know if you will understand me and if the poet is indulgent with my daydream. But very often the least verses of Les Éblouissements made me think of these giant cypresses, these pink sophoras that the art of the Japanese gardener makes hold, a few centimetres high, in a porcelain cup of Hizen. But the imagination which contemplates them at the same time as the eyes, sees them, in the world of the proportions, this is what they are actually, that is to say, immense trees. And their large shade as the hand gives to the narrow square of ground, plait, or stones where she walks slowly, days of sun, its dreams free of time, the extended and the majesty of a vast field or bank of some large river.") [Babelfish translation then edited by RJB] "For the 1994 edition of this review, Proust's editor explains that Hizen was the Kyushu region famous for producing the finest Japanese porecelain. Why does Proust even mention the provenance of the ceramic container? What matters to him is the conjunction of nature and art. The small tree, shaped to resemble the giant cypress, is set or based in the finest example of Japanese porcelain artistry. As art the bonsai is greater than nature because free of time (in "ses songes plus que centenaires"), set in art to invite the imagination to recreate the centuries-old cypress in the mind. And even as nature the bonsai is less than real, being an iconic representation of the other, greater reality of the giant tree. The art of bonsai, particularly its dual essence as art-nature, induces in Proust in 1907 a "rêverie" which he is not sure the reader will understand ("Je ne sais si vous me comprendrez"), but which he will continue to develop in his novel." 2 "Oh, dear, at the Ritz I'm afraid you'll find Vendôme Columns of ice, chocolate ice or raspberry... Those mountains of ice at the Ritz sometimes suggest Monte Rosa, and indeed, if it's a lemon ice, I don't object to its not having a monumental shape, its being irregular, abrupt, like one of Elstir's mountains. It musn't be too white then, but slightly yellowish, with that look of dull, dirty snow that Elstir's mountains have. The ice needn't be at all big, only half an ice if you like, those lemon ices are still mountains, reduced to a tiny scale, but our imagination restores their dimensions, like those Japanese dwarf trees which one feels are still cedars, oaks, manchineels; so much so that if I arranged a few of them beside a little trickle of water in my room I should have a vast forest, stretching down to a river, in which children would lose their way. In the same way, at the foot of my yellowish lemon ice, I can see quite clearly postilions, travellers, post-chaises over which my tongue sets to work to roll down freezing avalanches that will swallow them up..." (126) 3 |

|

1

"Marcel Proust," Wikipedia.

Image from here. |