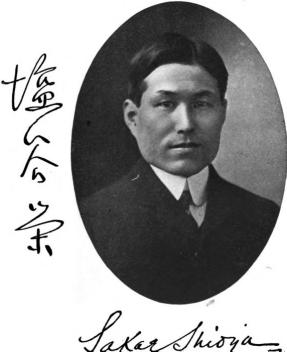

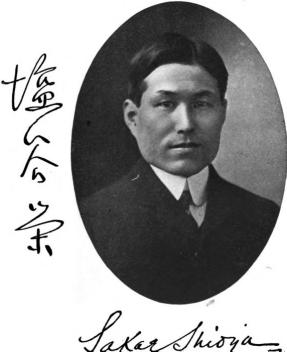

| Sakae Shioya was born fifty miles from Tokio, and at the age of twelve began the study of English at ? Methodist school. Later he studied natural science in the First Imperial College at Tokio, after which he taught English and mathematics. He came to America in 1901, received the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Chicago, and then took a two years' post-graduate course at Yale, and returned to Japan to devote himself to literature and the drama. Shioya wrote the Preface for When I Was a Boy in Japan from Yale University in 1905; on pg. 9 he states that "and then I don't want to disclose my age." We can deduce that he probably was born no later than the early 1880s and that the quoted incident below took place no later than the mid-1890s. He helped translate Nami-ko by Kenjirō Tokutomi in 1905, did a translation of The Pagoda by Rohan Kōda in 1909, and then edited a volume of Chûshingura by Hiroshige Andō in 1940, among other works. This latter book saw several editions into the mid-1950s. 1 |

| When I Was a Boy in Japan

by Sakae Shioya CHAPTER VII, AN EVENING FÊTE (1906): EVENINGS were not without enjoyment for me. And for this I owe much to my father. My father was a silent, close-mouthed man. His words to children were few and mostly in a form of command. They were never disobeyed, partly because it was father who spoke, but more because we knew that he spoke only when he had to. Indeed, he carried a formidable air about him, apparently engrossed in thought somewhat removed from his immediate concern. He was by no means philosophical, however, and his reticent habit was born of the peculiar circumstances under [92] which he was laboring. Fortune was evidently against him. And partly out of sympathy with him and partly out of fear of breaking his spell, when we had something to ask of him -- boys have many wants -- we had some indirect means to devise. Thus, when my cap had worn out and I wanted a new one, I dropped a hint in his presence by way of a soliloquy: "I wish I had a new cap. My old one is worn out." Saying this just once at a time and thrice in the course of one evening, if I persevered for three nights, I used to have my old cap replaced with a new one on the next day! He knew that he was fighting against odds, but his spirit was never crushed. He only persevered. One day he came back from his evening stroll with a piece of bamboo flute. Evidently he was attracted by a tune a man at the corner of a street was playing on it as he sold his wares, and felt his soul suddenly gain its freedom and soar to the sky. I remember how well he loved [93] his instrument, and from day to day he used to pour out low, mournful tunes. But his art was never equal to the demand of his soul, and one evening the bamboo flute was laid aside for a pot containing a dwarf pine-tree. You may well wonder how a flowerless potted tree could be preferred to even the commonest tune for spiritual solace. But at any rate it was a piece of nature, and was healing to behold. And then, in its fantastic shape, there was a beauty of repose which had a very soothing effect, but which required some study for appreciation. But in his case, there was something deeper in the matter. A tree over fifty years old, which, if left in the field, would have grown to an immense size, was reduced by human art to only a foot in height, and was kept alive on a potful of earth. My father must have read a history of his own in it and tried to learn a secret of contentment from it. One by one potted trees were added to [94] his stock, -- he could afford to buy only at odd intervals, -- and presently shelves were provided for them in the small garden. Morning and evening he attended to them, and with patience as well as with pleasure looked forward to the time when his care would result in a growth of just an inch and a quarter of pine leaves and palm leaves two inches by three in size. One night an unexpected thing happened. A thief found his way to the garden from the back door and sneaked away with half a dozen of the choice trees. Naturally, my father was distressed, but after a while he was patiently filling the vacancy one by one, of course seeing that the back door should be securely locked every night. I was going to tell you something about the amusements I had in the evening, but it was mainly due to this love of my father's for potted trees that I was taken regularly to a local fête, held three times a month. The day for this was fixed; it [95] fell on every day connected with the number seven; that is, the seventh, the seventeenth, and the twenty-seventh. And as in the calendar, rain or shine, it came and went. Naturally, I had my weather bureau open on that day to see if the evening was all right, for a wet night would be an irretrievable loss. At the police stand they published a forecast in the morning, but that was not to be too much relied on. It sometimes said rain when it was anything but wet, and fine when it was actually drizzling -- though in the latter case I rather inclined to believe the report even if it ended in sorrow. I did not need any formality of asking to be taken; it was a matter of course with me as long as I behaved well. This behaving, however, was peculiar. I had to be waiting for my father outside and follow him when he came out, without saying anything or shouting for delight for a block or so. The reason for this was simple. Mother objected to sending out the [96] younger members of our family in the evening, and especially to such a crowded place where they were liable to be lost. My going there must not attract their attention. One evening I slipped off with my father in this way. The place where the fête was held was not far away, and after two or three turnings we soon came to the street. At a distance, you might take it for a fire, for the tiny stalls and booths crowding the place were lighted by hundreds of kerosene torches which flared and smoked. The central section of the street was not more than two blocks in length, but it was literally packed with six rows of booths and stalls and with such a concourse of people that there did not seem to be room even to move. The approach to the scene was marked by some show booths. Hung in front were some wonderful pictures of what was to be seen within... [97] ... [98]... Now a great part of these enterprising peddlers were gardeners by profession. And out of the six rows of booths in the central portion three were shows of potted flowers and trees. They even had for sale grown-up trees half as tall as a telegraph- pole! As we came to this part my father slackened his pace. Here was something at last which interested him. He took time to examine some of the nice potted trees, [99] and his progress was very slow indeed, somewhat to my annoyance. I would rather have him stop before a candy booth than in these places. After a while, however, he found one tree much to his liking. He was tempted just to ask the price of it. "Ten dollars, sir," was the answer. My father smiled dryly and passed on. "How much you give, Mister?" asked the man. No answer. "I'll make it five dollars this time, Mister," cried the man. Still receiving no answer, he came after us. " But give me your price, Mister." " Fifty cents," said my father. " Ough, that won't pay even the express. Give me a dollar, then." But my father was already some distance away. The man, growing desperate to lose him, cried aloud: " Mi-ster, you can have it for the price. [100] This is the first one I have sold this evening. I must start the sale, anyway." So my father came into possession of one more potted tree. The price was low, to be sure, but the man did not undersell his goods. There seemed to be nothing now to do but to wend our way home as my father turned round at the corner and came down with the crowd. We passed toy booths, basket booths, booths where hairpins with beautiful artificial flowers were sold, or where all sorts of fans, bamboo screens, and sundry other things were for sale. And we passed them apparently without any interest, at least on my father's part. I was wondering what my father would buy for me, when whom should I meet but my aunt and Tomo-chan just going round the street in the other way? I spoke with Tomo-chan while my father and aunt were exchanging some remarks -- possibly about the potted tree. 2 |

|

1 The Publishers' Weekly, Oct. 6, 1906 (No. 1810), pg. 973. 2 Shioya, Sakae When I was a Boy in Japan (Boston: Lothrop, Lee &

Shepard Co.; 1906), pp.

91-100.

B&w photo from Frontispiece. |